In the 19th century, Boston had a major problem, particularly in the Back Bay: it smelled. No, it stank!

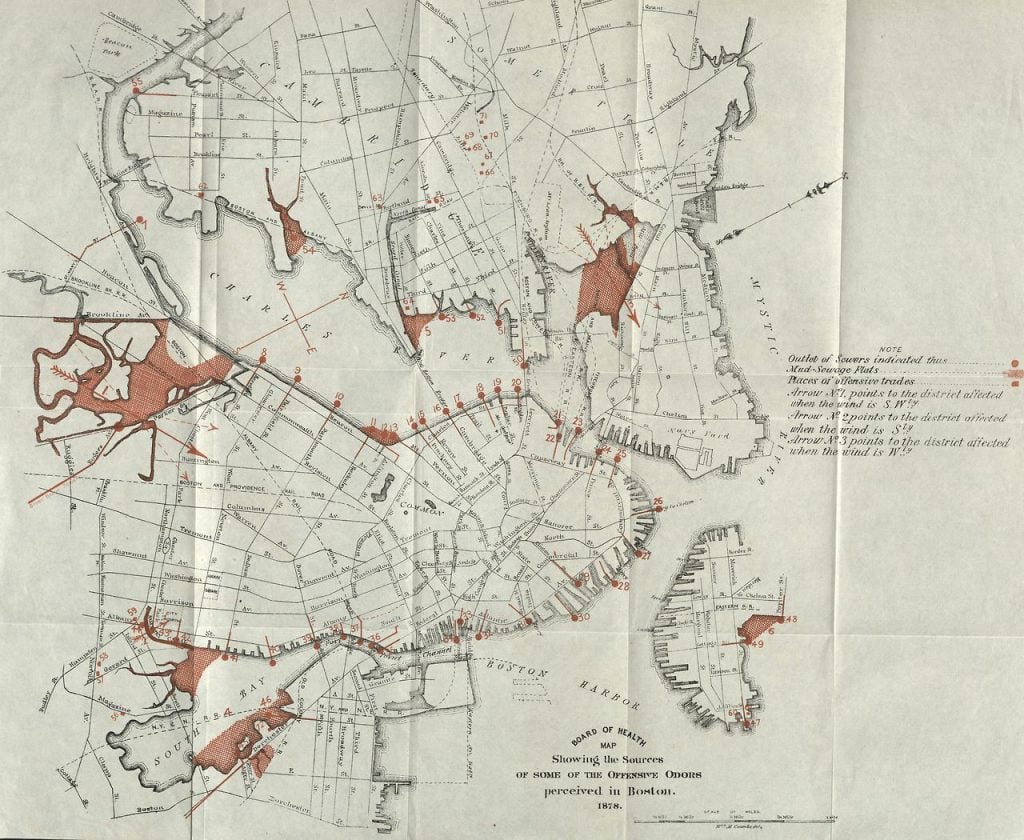

This wasn’t always the case. Along the back side of the peninsula where Boston stood, what we call the Charles River, Muddy River and Stony Brook would naturally flow into the tidal flats of the Back Bay area. But in the 1800s, the construction of a mill dam with a toll road to connect Boston and Watertown blocked the waters (and a growing population’s waste) from escaping out to sea. Landfill of the tidal flats begun in the late 1850s to create the Back Bay neighborhood only decreased the flow and increased sewage. The available land around the flats was unlivable, particularly in the warmer months, and could only be used for industry. (Think carriage garages where the smell of horses was far enough from the noses of wealthy carriage users.) By 1878, the city’s Board of Health even published a map of “Some Offensive Odors” where these flats (at left) are the largest red mark on the city.

Boston City Archives

Boston’s shortsighted growth was literally fouling its ambitions to grow more—and better. City officials wanted to, and had the money, but were limited by the Back Bay “stink!” and the limited amount of land above the flood lines for expansion. So, they set out to do something about it. Headed by Charles H. Dalton, a park commission proposed a citywide park system by 1875, and reports show they immediately chose to start with the smelly basin of the Back Bay as “a matter of sanitary necessity.” Frederick Law Olmsted was soon called to advise the commission, and in 1878 hired to draw up plans. Given he had grown up exploring the salt marshes of Connecticut, and had been innovating drainage and water management in major park projects for nearly two decades, Olmsted was the most likely expert to solve Boston’s smelliest problem.

By 1879, he developed a plan that solved three major challenges—tides, stink, and usability— through one multifunctional landscape design that combined both flood control with sewage treatment, all brilliantly disguised as a beautiful, usable landscape of variously elevated paths and parkways around a meandering water feature. The deeply dredged bowl shape of the park allowed for tidal flood waters to be contained as needed, while gatehouses controlled entering water (and sewage) to within a height variation of a single foot. Olmsted named the site not a “park” but “The Fens” (an Old English word for “marsh”) and the curving parkway around the edge was named the Fenway.

One end of The Fens linked to Olmsted’s Charlesgate Park, the literal gate connection that controlled water flows with the Charles River, and the metaphorical gateway connector to the city’s extent parks: the Commonwealth Avenue Mall, the Public Garden and Boston Common. The other end of The Fens extended as the linear park system Olmsted designed along the Muddy River, which wound its way between Brookline and Boston along the Riverway to Jamaica Pond, with parkways connecting to the Arnold Arboretum, and the Arborway connecting to Franklin Park, the “great country park.” Olmsted’s original plan called for a U-shaped necklace of greenspaces around Roxbury, the original “neck” of Boston, which terminated at South Boston’s waterfront. The final link, the Dorchesterway, was never realized.

a matter of sanitary necessity

While it took decades to design and construct what today is called the Emerald Necklace, it’s humble beginnings of “stink” have truly transformed Boston. Looking closely at what developed around the The Fens, we can see how much foresight Olmsted put into his design intended to work with, and not against, the natural flow of the site. He explained in 1880 the choice to use the salt marsh feature as “a direct development of the original conditions of the locality, in adaptation to the needs of a dense community… possibly to suggest a modest poetic sentiment more grateful to town-weary minds than an elaborate garden like work would have yielded.” Once complete in 1893, the site became the destination for some of the city’s most inspired, educational and innovative institutions, including:

The Massachusetts Historical Society sold its Tremont Street Headquarters in 1897 and moved to it’s Boylston Street location in 1899.

The Museum of Fine Arts purchased the land on The Fens in 1899 and moved from Copley Place to its current location by 1909, with a wing built to face The Fens by 1915.

Isabella Stewart Gardner likewise purchased land on The Fens in 1899, and built her palazzo Fenway Court, which opened as a public museum in 1903.

Simmons College then purchased the land next to Mrs. Gardner’s and built their main college building in 1904. Numerous education campuses then joined the area.

- After planning since 1902, the new campus for Boston Normal School and Girls Latin School (later Boston Latin Academy) opened in 1907 at the site now occupied by Massachusetts College of Art;

- Wentworth Institute was chartered in 1904 and opened its doors on Huntington Avenue across from the Museum of Fine Arts in 1911;

- also in 1911, YMCA Boston began construction on its current Huntington Avenue complex and its educational programs were incorporated as Northeastern College in 1916;

- by 1919 Emmanuel College opened at 400 the Fenway;

- eventually Boston Latin School moved from the South End to its current location in 1922;

- and the Museum of Fine Arts hired Guy Lowell to construct its School at 230 Fenway by 1927.

Harvard Medical School moved from Copley Square to its newly built Longwood campus in 1906 with opened land between Olmsted’s completed Fens and Riverway, drawing many other hospitals to the site, now known as the Longwood Medical Area.

At the other end of The Fens, the land at 140 Fenway was purchased in 1911 and by 1914 opened as the Forsyth Dental Infirmary for Children

But the most notable occupant of the area may be its namesake, Fenway Park, home to the Boston Red Sox. Since their founding in 1901, the team had played at the Huntington Avenue Grounds through 1911 (the ground of historic wins including the first World Series in 1903) until the Huntington’s grass sod was brought to the team’s “new” field in 1912.

Olmsted’s Fens neighborhood had become a major magnet for the city, state and region as a world renowned medical, educational, cultural and residential community. Boston’s initial financial investment in Olmsted’s landscape has led to generations of innovation that has reaped dividends of economic support back into the city. And, through Olmsted Now, we are rediscovering the value and impact of Olmsted’s brilliant designs in new, different and contemporary ways.