Karen Mauney-Brodek (KM): For the last many decades that you’ve been in Boston, you’ve been advising and shepherding a part of the dialogue here in the city. And as you look back, what do you think the themes for open space are today that we’re wrestling with? And what do you think should be our goals and challenges as we look into the future?

Ted Landsmark (TL): I think that over the last half century the city has seen a sharply increased appreciation of the value of parks and open space. We didn’t invest in parks in the way we see investments now in parks. Relatively small budgetary investments have large policy and political returns for public officials who make them.

Even in cities, people love their trees and open spaces. When a park re-emerges in or is improved within a neighborhood, it is almost immediately beloved, particularly by residents who had a stake in how that park was developed.

We’ve seen an evolution: Boston now has parks and open space that are more readily available than virtually any other city in America. Some of those spaces are small but they are much beloved and very heavily used. And of course, what we found during Covid was that they became the common ground where people felt safe. And safety in open spaces has clearly become one of the priorities, as has the inclination to think more about parks.

Erin OToole

KM: We’re both on an advisory committee to Acting Mayor Kim Janey on climate. I think a lot about access to water. I grew up in downtown Atlanta and I’ve been surprised by the lack of public pools or places to cool off in Boston. It seems to remain segregated in the city.

TL: But there are other ways of accessing the water in Boston and we don’t do enough to publicize those. I’ve been out to the end of the Marine Industrial Park, now the Flynn Park. I am inevitably surprised, I shouldn’t be, when there are people fishing there, of all ethnicities. I keep wondering; How did they find this place? There’s no signage that directs you.

KM: Definitely. I lived in New York and everybody knows Coney Island. It’s communicated. And the subway goes there. But here, accessing the water, our history, it does feel a bit more underground.

TL: I look at Muslim families, couples, wheeling their kids along the edge of the beach while planes are coming in over them. And it is such a different image in Boston than Boston has of itself. You know, East Boston has not been an Italian neighborhood in a quarter of a century and yet people still think of it as such. I am convinced that we need to do more publicity and more memorialization commemorating: How have the neighborhoods changed and who was there?

I think of the sheer number of institutions and universities here, and how this is a world class city and the world is here. When I first moved here, I briefly lived in the Fenway. And I had never lived in a building that was so full of everyone in the world. But I heard Boston was not an integrated city. I don’t think we shine a mirror back at ourselves enough.

KM: Definitely.

TL: Well, Boston, it has been more tribal in a disapproving way. That is to say the city historically has done a good job of telling people where they are unwelcome. I’ve heard on several occasions that there are very diverse kids living in the housing developments in Southie. That wasn’t always the case thanks to Doris Bunte and others. Now, there are lots of black and Latinx kids and Asian kids growing up in those projects. They are two or three blocks from Carson Beach, where Mel King took demonstrators to remind everyone that those beaches belong to everyone.

Later, when at the BAC [Boston Architectural College], I remember having a summer cookout at Carson Beach and some of the black employees came to me and expressed discomfort about whether we were safe going there. But in getting there we found out that the vendors were diverse and that everyone is now using that beach.

But going back to the diverse kids growing up in those projects, they can look across the harbor and see downtown. And they can actually walk to a red line station two or three blocks away and be in downtown in 15 minutes. And yet the majority of those kids have never been in downtown Boston because they say they’re afraid to go there. Now that’s a city that clearly needs to use its open spaces and its transportation systems to create linkages among and across neighborhoods in ways that enable people to feel that the whole city is open and accessible to the parks.

That’s what developers and planning agencies need to think about: How can we address affordable housing issues by building more along open space to actually connect neighborhoods.

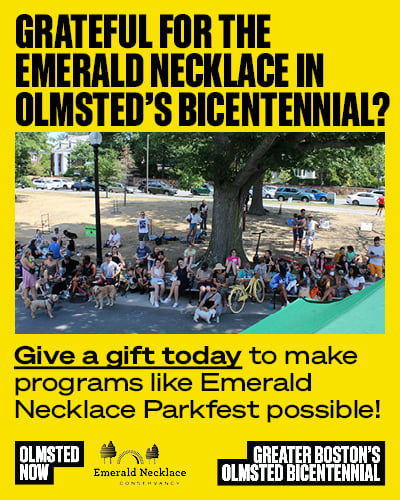

Growing up in East Harlem, I used my bike through Central Park to access and to learn about Bergdorf Goodman’s right on 5th Ave. The park made it possible not the streets. I see that in the work we do with the Emerald Necklace: It enables people, particularly of limited financial means, to feel that they can access anywhere in the city and that it’s going to be welcoming.

KM: I’ve worked for two city parks departments before now, and what you are saying makes me think we need to flip the culture of park signs that lead with “No” this or “No” that. There should be signs that say “Yes” to the following: “Yes” to joy. “Yes” to being here with your family; “Yes” to creating art here; “Yes” to using this space to discover new neighborhoods. How do we create a culture of “Yes” in our parks and really provide a sense of welcome, as well as history? Even if, as Mitchell Silver says, some activities are not welcome in parks, we need to emphasize that all people are welcome. How do we better communicate this—and make it a reality?

TL: Yeah, for me, everything comes down to the picture I took of a guy in a wheelchair at the edge of Leverett Pond. You know it was a motorized wheelchair so he had a little help to get there, but it was pretty clear to me it was not the first time he’d been there. He was there feeding the ducks, and for him it was the opportunity to share in the magic. We believe that our parks are all open and welcoming. We just need to make it so.