Frederick Law Olmsted holds the rare distinction of inventing a professional field and then taking all the orders. And the better for us. The winding paths, rich foliage and sun-dappled shadows inherent to his work still hold sway over tourists and residents of cities across the country today. His parks have even greater impact now, as the cities have grown around each of his designs. Next April is his 200th birth anniversary, and I think now is the time to assess how his designs work for our society today, or not.

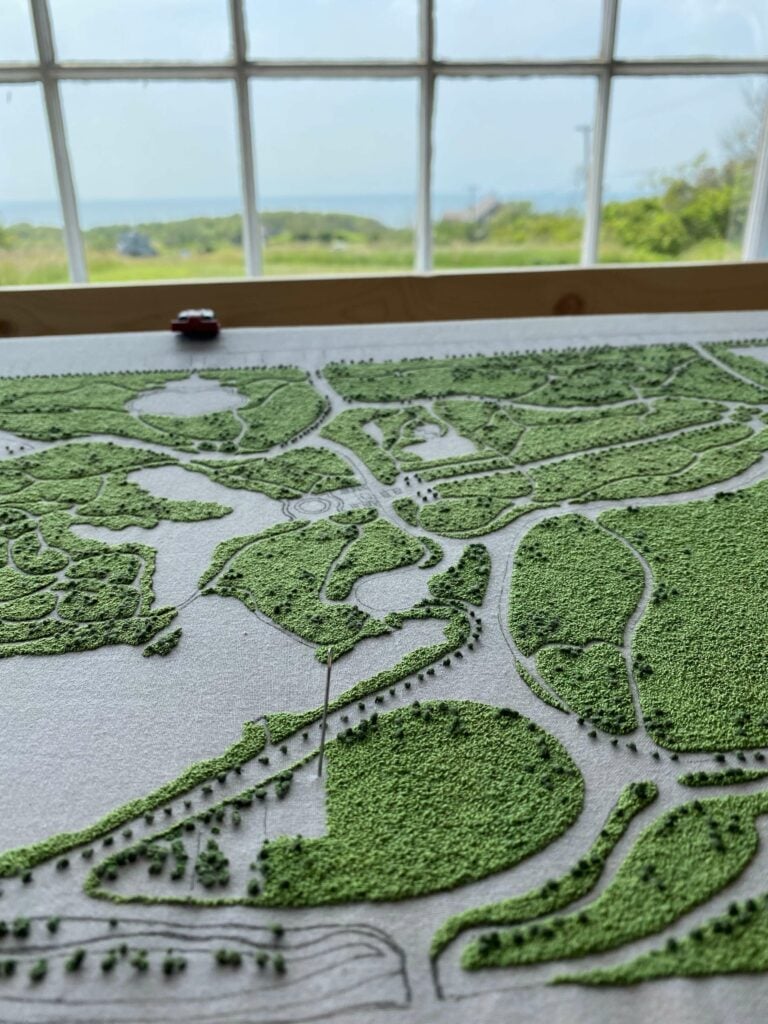

I’ve spent almost 4 years hand sewing tapestries of Central Park and the Emerald Necklace Park system in Boston. I’m self-taught as of 2018, but my Master’s degree in Environmental Conservation Education from NYU (2016) has been a big inspiration and motivation in my career. I’m fascinated by Frederick Law Olmsted’s personal story – I identify with his early struggles and his lifelong passions – and I have been using my embroidery to draw attention to the lasting impacts of his work. His vision literally changed the face of America, absolutely for the better. Today, most urban Americans live in or near one of his constructs, or those of his firm, and yet he is relatively unknown.

When I discuss Olmsted’s impact with “regular” people, there are two things I try to highlight. The first is that his landscaping vision addressed a very new problem for humanity – too much distance from nature. Humans had, through the agricultural and industrial revolutions, so secured themselves from natural disaster, that they were at risk of harming themselves. This counterintuitive foresight of Olmsted seems basic, in retrospect, like an impressionist painting. But it is hard to overstate the positive impact of his vision.

I do not think of grass lawns in urban parks as undeveloped – I see them as unfinished.

Park quality and access has a direct correlation to quality of life for individuals and communities, for several reasons. Exercise, recreation, and reduced pollution can dramatically improve physical and mental health, and ultimately improve economic output. America is especially fortunate: we are running out of undeveloped land, but we already have many large, beautiful parks to enjoy.

Beyond enjoyment, however, government is responsible for ensuring a secure food system, which is now global and now consists mostly of giant commercial farms or small sustainable gardens. There is no middle ground left – especially when most undeveloped land goes towards housing, or remains undeveloped for the sake of ecological integrity. This is good – we must leave undeveloped land alone, as much as possible, or risk animal to human disease transmission. However, I do not think of grass lawns in urban parks as undeveloped – I see them as unfinished.

A garden seems like a small goal… but even a small food garden in Central Park is a big deal, and requires considerable political momentum.

It is true Olmsted was frustrated, in his late years, by failures to implement his designs brick for brick. But I think he would see the difference between failure to implement, and necessity to renovate. And his whole obsession with landscape arrangement can be traced to his driving impulse, to build green spaces that benefit the health of stressed-out or chronically ill urban residents, like his mother and brother, who both passed prematurely. I truly believe that such a compassionate human would not elevate the purity of his design above the integrity of our national security, and our food system.

The price of food has climbed faster in the last 10 years than in any decade since World War II, and as we have seen during the pandemic, our global supply chain is seriously susceptible to bottlenecks and disruption due to natural disaster. Even beyond the rationale of diversifying our food stock, and the many other financial and logical reasons to grow food in Central Park, there is an emotional and human argument, too. Frederick Law Olmsted cut his landscape design teeth by working as a farmer in New England, at a time when 70% of the country derived their main income from farming. I think he would be shocked to see what the food system looks like today.

Olmsted is not the one making the decisions now, and it is hard to say who exactly will step up to this. But I have some good news. I want to help fund this change, through a donation. I started sewing my table runner without knowing how long it would take, but I didn’t care because my Brooklyn-born Grampa had just passed and I was grieving too hard to comprehend the task before me. Anthony DeSantis was a first-generation Italian American who put himself through City College of New York by working as Chef de Cuisine at the Waldorf, then paid for Yale Architecture School by working as an EMT. He eventually designed the National Geographic Museum and the Kennedy Center. Most importantly, he taught me how to cook. I can think of nothing better to honor his memory than to donate my table runner for a fundraiser for a garden in Central Park.

There is plenty of room on this hill. A garden seems like a small goal, compared to Olmsted’s work, or my Grampa’s, but even a small food garden in Central Park is a big deal, and requires considerable political momentum. I hope after reading this story you feel empowered, and perhaps inspired to share this project with the landscape architects and policy makers in your community. And I invite you to come discuss with me in person, at my next pop up on August 28, 2021 in Medford. I know this common-sense campaign for urban gardens in landmark parks will most likely last my whole life, but if we cannot grow food in our Historic Landmark parks, our monuments to nature, they will become memorials to us.