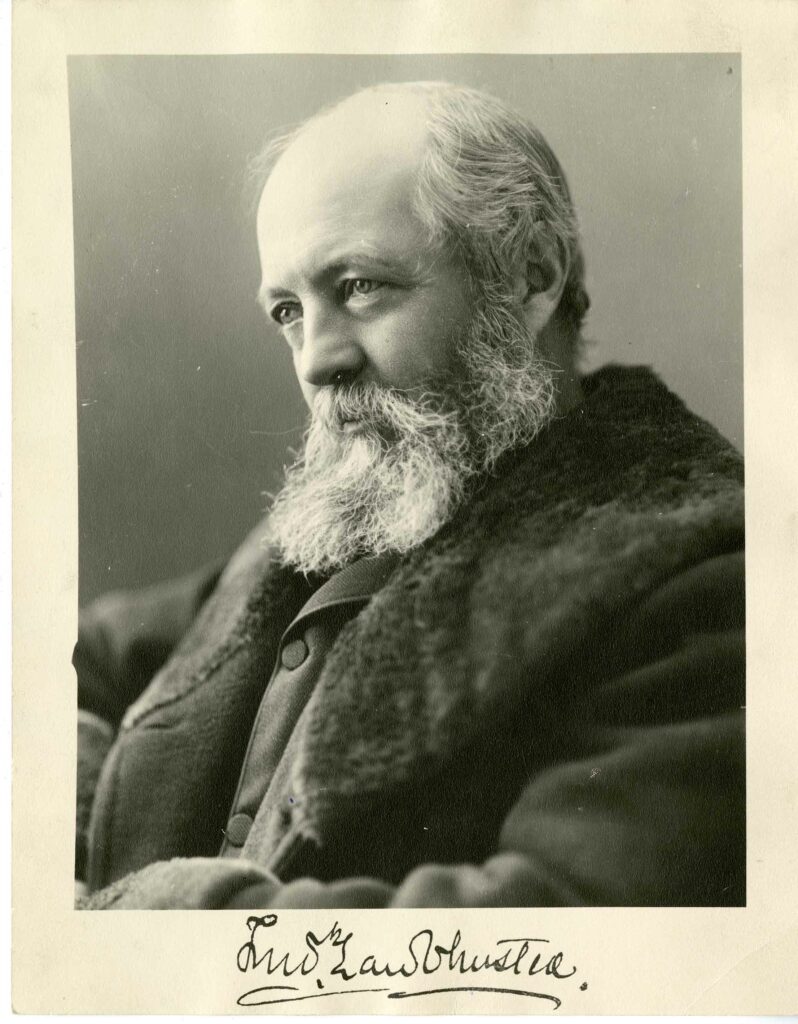

“Nothing else compares in importance to us with the Boston work, meaning the Metropolitan quite equally with the city work. The two together will be the most important work of our profession now in hand anywhere in the world.” (Olmsted, 1893)

At the end of his career, Olmsted made two lasting shifts in his practice—partnership and location. For his Boston work and onward, Olmsted incorporated and credited the support of his mentees as partners, including his oldest stepson John Charles, his younger son Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., Henry Sargent Codman (Charles Sargent’s nephew) and Charles Eliot (who studied horticulture at Harvard). While his projects with longtime peers Sargent and Richardson would continue—including stations for Boston & Albany Railroad that inspired the Railroad Beautiful movement—Olmsted’s relationship to this next generation of designers was pivotal to his legacy. As he was winding down, he had more perspective on the profession and what his firm was already doing in the Greater Boston area, writing to his partners in a letter:

“In your probable life-time, Muddy River, Blue Hills, the Fells, Waverly Oaks, Charles River, the Beaches, will be points to date from in the history of American Landscape Architecture, as much as Central Park. They will be openings of new chapters of the art.” (Olmsted, 1893)

Olmsted’s instinct to pass on his priorities, values, experience—even his name—is what established the first professional architecture firm in the nation and its lasting impact across the country.

The location of this firm was, not surprisingly, footsteps from Sargent and Richardson’s home offices. By 1883, at age 61, Olmsted permanently moved his family and professional life from New York to 99 Warren Street in Boston’s neighboring town of Brookline. The property, with a farmhouse on nearly two acres, was owned by two elderly sisters not inclined to sell. Olmsted struck a deal in which he could purchase the land if John Charles designed a cottage for the sisters to live out their days at the edge of the property rent free. Olmsted named the site “Fairsted” and began redesigning the grounds and home into an office to continue his Boston work.

Soon Fairsted had a new neighbor, Isabella Stewart Gardner; notably, she was also early to purchase land along Olmsted’s completed Fens project in 1899 for the public museum she opened as “Fenway Court” by 1903. (In her collection is a birthday book with signatures, including Olmsted who filled in the empty date before his own birthday April 26.) The neighborhood friendships anchored Olmsted but none more so than with Richardson whose untimely death in 1886 was a deep blow. Olmsted remembered his friend with superlatives:

“He was the greatest comfort and the most potent stimulus that has ever come into my artistic life,” (Olmsted, 1888)

Even as Olmsted entered the final decade of his career, his work in Boston was paralleled by numerous nationally significant commissions, including—preserving and designing Niagara Falls as the country’s first state park, planning the campus of Stanford University, developing the fair grounds and lagoons for the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, and planning the grounds for Biltmore, George Vanderbilt’s 125,000 acres in Asheville, N.C., which became the model of American reforestation and scientific forestry. This said, Olmsted was unwavering with his firm that the ultimate priority had to remain Greater Boston. Again, from his 1893 letter to his partners, he implored:

“I would have you decline any business that would stand in the way of doing the best for Boston all the time.” (Olmsted, 1893)

Upon his retirement in 1895, Olmsted had completed approximately 500 public and private projects in his career, including parks, campuses, suburbs, rail stations, fairgrounds and many other types of outdoor spaces. Fairsted remained an active firm under the Olmsted name through 1979, with 2,162 projects in Massachusetts and over 5,000 across North America. History continued to be made through Olmsted’s partners and successors. Charles Eliot founded the first public land trust in the nation and largest in Massachusetts and also advocated for linking greenspaces beyond Boston to the surrounding region in what became the Metropolitan Park System. John Charles Olmsted was a founder and first president of the American Society of Landscape Architects. In 1900, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. established the first academic program in landscape architecture at Harvard and was instrumental in founding the National Park Service and defining its mission in 1916.

2,162 projects in Massachusetts and over 5,000 across North America

Ultimately, Olmsted instilled the field of landscape architecture with a lasting philosophy and purpose: respect natural site conditions in designs that provide restorative public experiences for the health of individuals and society as a whole. Looking back on his own career, Olmsted saw clearly, even as definitions of “parks” and their use were still blurry, that broad interest in natural landscape—a “park movement”—was not just a “luxury,” but a fundamental civic need:

“Considering that it has occurred simultaneously with a great enlargement of towns and development of urban habits, is it not reasonable to regard it as a self-preserving instinct of civilization?” (Olmsted, 1880)

The 2022 bicentennial is an opportunity to consider Olmsted’s question about the need for parks and greenspace today. It is a moment to look with fresh eyes on his 19th-century ideas and apply the most equitable principles for public health, social health and democratic access to the 21st century. Olmsted Now is an opportunity to advance renewed ideals of shared use, shared health and shared power in parks and open space. Now is a new generation’s chance to answer Olmsted’s call:

“It is open to question whether we care much more than our ancestors did for all manner of beauty of nature.” (Olmsted, 1880)