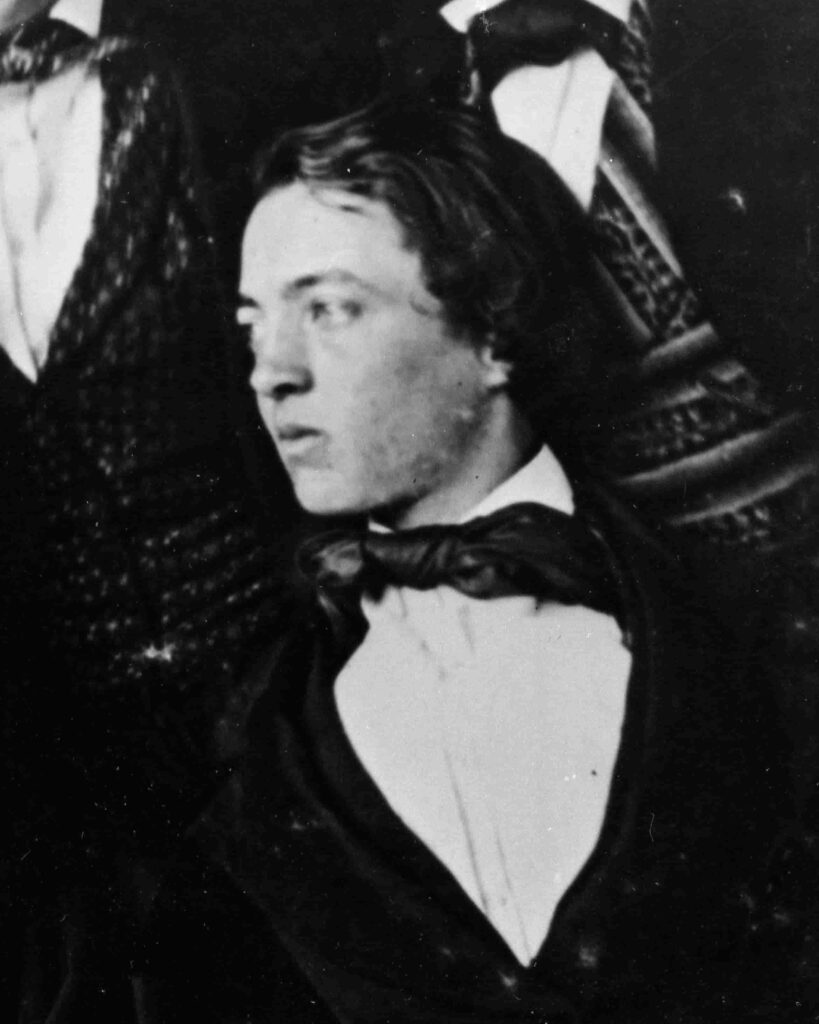

“I want to make myself useful to the world—to make happy—to help to advance the condition of Society and hasten the preparation for the Millennium—as well as other things too numerous to mention.” (Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., 1846)

When, at age 24, he wrote these words to his friend, Olmsted already had earnest ambitions for service that would make a lasting impact for generations to come. Now nearly two centuries later, countless people have encountered the legacy of more than 5,000 landscape projects that Olmsted, his sons and his successor firm designed across 47 U.S. States and several countries. When they step into an Olmsted-designed park, parkway or neighborhood, people not only enter into a physical space but engage with his fundamental idea: access to open space can improve lives—physically, socially and civically.

This idea emerged through first-hand experience. Traveling in England in 1850, Olmsted and his brother visited farms, castle grounds, botanical gardens, an arboretum and more, but he was most struck by England’s first publicly-funded park which had opened just three years prior in Birkenhead near Liverpool. He noted the brilliant engineering and design: earth from an excavated pond made a variety of surface mounds “done with much naturalness and taste” and all “thoroughly under-drained.” Along with these details, what would stay with Olmsted was a bigger idea: egalitarian space is possible. Commissioned even under a monarchy, Birkenhead signalled something that thrilled and prompted him to later write:

“I was ready to admit that in democratic America there was nothing to be thought of as comparable to this People’s Garden… All this magnificent pleasure-ground is entirely, unreservedly, and forever the people’s own. The poorest British peasant is as free to enjoy it in all its parts as the British Queen.” (Olmsted, 1851)

Olmsted’s lifetime, 1822-1903, paralleled the rapid expansion of U.S. cities and American democracy itself. His childhood in the Hartford, Connecticut countryside and his many early professional forays—including as an apprentice seaman on a tea ship to China; as a surveyor and experimental farmer who innovated irrigation drainage; as a young journalist who reported on Southern slavery for what became The New York Times; as head of the U.S. Sanitation Commission (precursor to the Red Cross) who directed systems to keep Union troops healthy in the fields of war; and as a mine manager in California—all informed his work designing green spaces for people, a practice he would eventually name “landscape architecture.” Olmsted’s vocation emerged just in time: as the nation was transforming from rural to urban and poised to battle over the true meaning of equal rights in open space.

egalitarian space is possible

As a journalist across the Southern states, Olmsted observed first-hand the relation of people to the landscape, particularly the injustice of slavery, noting “there is no apology for it.” Despite excuses of kind treatment to slaves, Olmsted could not reconcile the indignity and inhumanity of forced relations to land and labor for someone else’s gain, and argued if a slave were free:

“If, especially, he had to provide for the present and future of those he loved, and was able to do so, would he not necessarily live a happier, stronger, better, and more respectable man?” (Olmsted, 1853)

Republished in 1860, Olmsted’s writings made the case for readers across the expanding U.S., and abroad, why slavery was irreconcilable with the nation’s economic, political and moral future. He put the urgent choice ahead of his countrymen in stark terms:

‘We had to subjugate slavery, or be subjugated by it.” (Olmsted, 1860)