In June 2018, after years of planning, two stages were erected at Franklin Park for the inaugural Boston Art & Music Soul (BAMS) Festival, a day-long celebration of Black artistry. Then came the rain.

Still, more than 2,000 festival-goers of all ages stayed to enjoy performances by more than 20 groups and musicians, most of them homegrown talents like Valerie Stephens, STL GLD, Latrell James, Oompa, Billy Dean Thomas, and RickExpress.

“The energy was so positive—there was so much love,” said Catherine Morris, founder and executive director of BAMS Fest, the organization that hosts the annual festival. “It drizzled the entire eight hours, but I was not going to cancel the festival come hell or high water.”

An event of such scale had not taken place at Franklin Park in decades. For Morris, who spent three to four years scouting venues, the location was a natural choice—one rooted in her own family traditions and in the larger history of Black Boston. It came at the suggestion of her mother, who recalled attending cultural festivals and concerts at the park’s Playstead Field in her youth.

“Walking those grounds, I said, ‘This is befitting.’ We’re standing on fertile ground of people who paved the way for me to even do what I do,” said Morris.

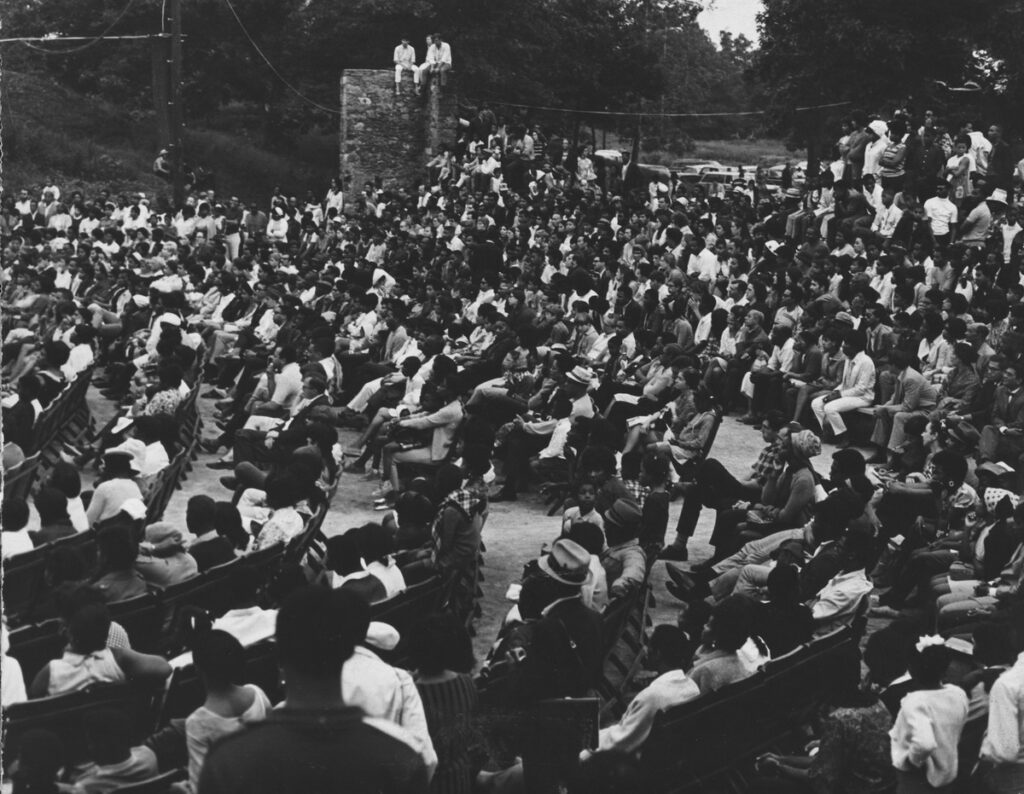

One of those pioneers in activating Franklin Park was Elma Lewis. A champion of arts education for Boston’s youth of color, Lewis founded the Elma Lewis School of Fine Arts in Roxbury in 1950 as well as the National Center of Afro-American Artists (NCAAA) in 1968. In 1966, she cleared out an overgrown and neglected area of Franklin Park—the ruins of the Overlook Shelter, destroyed by a fire in the 1940s—to create an open-air venue. Until the late 1970s, her Playhouse in the Park hosted nightly summer performances, bringing legends like Duke Ellington, Odetta, and the Billy Taylor Trio to Boston.

“She saw something that people didn’t see about the potentiality of what Boston could offer, so long as we could acknowledge collectively the contributions that Black arts, culture and identity have given to this city and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts,” said Morris. “For me personally and professionally, being able to add on to that legacy is so crucial right now. If my generation and the generations after don’t keep up the education—or ‘edutaining’— part of her legacy and what Franklin Park means, it’ll be lost forever.”

Morris, who grew up using the park for family cookouts and talent show practices, has watched gentrification rapidly change the surrounding neighborhoods. Her mother’s recollections of frequent festivals and concerts took her by surprise—it was a different time that she wishes she had experienced.

“I think that inconsistency [of programming over the last 60 years or so] really created a sense of hopelessness for a lot of communities, a sense that Franklin Park is a space that’s constantly overlooked,” she said. “I think ownership is really in question right now—in terms of influence about process or having access to the park, there’s no ownership in that. Communities need to have a seat at the table, from beginning to end—from the ideation process to acquiring permits and licensing.”

Morris hopes to see cultural programming pop up more frequently inside the park. Diverse leadership and community input could expand the small roster that currently includes BAMS Festival and the Franklin Park Coalition’s Elma Lewis Playhouse in the Park, which has revived the late activist’s summer concert series on a smaller scale. She sees outdoor plays, for one, as an opportunity to foster a sense of belonging for communities of color by rewriting the script on traditional theater etiquette, long determined by white audiences. Her wish list also includes a permanent structure for hosting a variety of performances inside the park, a revival of what she calls Lewis’ “amphitheater”—the playhouse stage at the Overlook Ruins.

“We have to be able to provide a variety of different infrastructures that allow communities to have as much access as possible, to be able to strategically program in those types of spaces in a way that is unprecedented—that is so futuristic that it conveys a sense of what is possible,” she said.

Communities need to have a seat at the table, from beginning to end

As for BAMS Festival, it has only continued to grow since that rainy first edition, bringing more than 8,500 people to Franklin Park for the annual event and joining forces with Berklee’s Beantown Jazz Festival. Despite having to cancel the 2020 and 2021 editions due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the festival has continued to highlight local talent through its virtual AMPLIFY THE SOUL series and in-person performances hosted in partnership with King Boston and the Museum of Fine Arts. Morris has plans for the event to expand beyond one day at Playstead Field: her goal is to grow it into a weekend-long affair, spanning the entirety of Franklin Park.

“We’re shifting the way that people experience festivals in Boston, particularly Black and brown communities, because for so long, dominant culture has said that people of color should only be able to experience arts and culture or music a certain way. We’re changing all of that just with our lineup, just by focusing on local artists, by incorporating dance and visual arts and food and vendors. That’s unheard of in Boston in particular,” said Morris. “It is a huge task but it’s one that we’re committed to, and we have seen the benefits it has given to the community.”