“It is practically certain that the Boston of today is the mere nucleus of the Boston that is meant to be.” (Olmsted, 1870)

Though he was known nationally by 1870, Olmsted’s Lowell Institute lecture “Public Parks and the Enlargement of Towns” for the American Social Science Association is what most directly introduced him to Bostonians. This was just as Boston had annexed neighboring towns and was grappling with how to connect the communities and introduce greenspace into its already crowded footprint. Olmsted laid out the three moral imperatives for urban parks—as a means to improve public health, social health, and democrative access to open space:

“To supply the lungs with air screened and purified by the trees, and recently acted upon by sunlight, together with the opportunity and inducement to escape from the conditions requiring vigilance, wariness, and activity toward other men—if these could be supplied economically, our problem would be solved… Especially would this be the case if numerous local grounds were connected and supplemented by a series of trunk-roads or boulevards… We want a ground to which people may easily go after their day’s work is done, and where they may stroll for an hour, seeing, hearing, and feeling, nothing of the bustle and jar of the streets.” (Olmsted, 1870)

He captured imaginations with his descriptions of how people could freely enjoy the parks: “several thousandlittle family and neighborly parties to bivouac at frequent intervals throughout the summer… Often they would bring a fiddle, flute, and harp, or other music. Tables, seats, shade, turf, swings, cool spring-water, and a pleasing rural prospect… supplied without charge.” The potential benefits of parks connected by tree-lined “Park-ways” inspired those eager to contribute to their city. Likewise, Olmsted’s resulting work and friendships with notable Bostonians allowed him to expand his thinking and imprint his practice upon the city in ways that resonate to this day.

Soon after botanist Charles Sprague Sargent was appointed as the first director of Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum, he wrote to Olmsted to help him realize what would become North America’s first public collection for the study of trees and woody shrubs. Olmsted, whose design philosophies encouraged people’s “unconscious or indirect recreation,” initially cautioned this may actually contradict assembling trees by taxonomy. Therefore, they would need to work closely together:

“Indeed a park and an arboretum seem so far unlike in purpose that I do not feel sure that I could combine them satisfactorily. I certainly would not undertake to do so in this case without your cooperation.” (Olmsted, 1874)

The Arboretum had an 1872 charter and donated land but needed broader support from city officials to be sustainable. By 1875, Boston had an initial proposal approved for a citywide park system and Park Commissioner Charles H. Dalton sought out Olmsted’s advice, formally hiring him by 1878 to design the entire system plan which would ultimately include the Arboretum, making it viable. While it took until 1885 to agree on a final planting plan that would balance Olmsted’s experiential and Sargent’s educational principles, the resulting Arboretum which combined winding paths toward breathtaking views with brilliant scholarship has been described as a collaboration where “form and function were woven together like a fine tapestry.” Though Boston’s is the only Arboretum designed by Olmsted, his success with Sargent proved (even beyond his own doubts) that he could integrate his aesthetics for people’s pleasure with scientific study, informing later arboretums in Buffalo and North Carolina.

In the same year Sargent had written to him, Olmsted’s dear colleague, architect Henry Hobson Richardson, took up full-time residence next to Boston in a hilltop Brookline home directly across from Sargent’s property. Richardson used this home as an officeand from its second story (it is rumored) he could view construction on his most acclaimed commission, Trinity Church in Copley Square. Back in 1865 in New York, Olmsted had met the younger Richardson returning from his architecture studies in Paris. At Olmsted’s recommendation, Richardson became his neighbor on then bucolic Staten Island, and they began suggesting each other for commissions—including the 1870 campus plan for Buffalo’s State Asylum, their first major collaboration. It would not be their last.

form and function were woven together like a fine tapestry

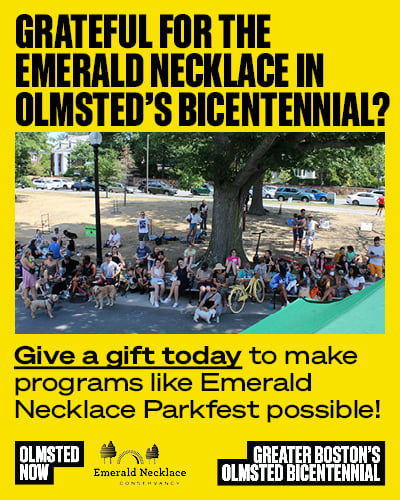

Just as Richardson’s work on Trinity Church wound down, Olmsted welcomed his expertise as work ramped up on Boston’s full park system—a decades-long project designing parks of various purposes to be linked via parkways connecting thirteen neighborhoods across nearly six miles to the city’s historic center. Olmsted’s linear park system is one of the first of its kind in the nation and realized his philosophies about public health, social health and democratic access in ways no single, larger or more central park possibly could. Rather than spite Boston’s geography, Olmsted found inspiration in the unique features of this water-bound peninsula whose downtown was connected by a “neck” to its growing body; he gave the city a “green ribbon” of continuous greenspaces known today as the Emerald Necklace.

Along with the Arboretum, Olmsted planned the city’s most expansive “country park” named Franklin Park, the site of the city’s largest natural freshwater spring known as Jamaica Pond, and the chain of waterholes, groves and meadows later called Olmsted Park. These he designed site-responsively to amplify existing geological features, such as puddingstone and glacial kettles, while also adding pathways, plantings and structures that appeared “natural.” That said, some of Olmsted’s Boston work demanded he not only amplify sites, but literally sculpt new formations: especially along Boston’s waterways, he introduced problem-solving innovations that laid the groundwork for what today is called green infrastructure.

he gave the city a “green ribbon” of continuous greenspaces known today as the Emerald Necklace.

First was Olmsted’s 1879 transformation of the Back Bay tidal sewage flats, that regularly flooded, into a pleasing greenspace with a winding water basin feature. In a report to Commissioner Dalton, Olmsted clarified this first project in the system would be unlike a traditional “park” with occupiable recreation spaces:

“The water in the basin will then have the general aspect of a salt creek, passing with a meandering course, for the most part, through or along the border of a sea-side meadow… The public cannot be prudently admitted to any part of the basin except the slopes of its rim. Passage across it must be by causeways and bridges. Its boundaries, which will be over two miles in length, may, however, be followed by wheelways, bridle roads and walks; and these, together with any needed passages across the basin, will command views over it, and may be shaded by trees.”(Olmsted, 1883)

Rather than call the site a “park”, Olmsted insisted that these “public grounds of distinctive character” be named for what they are—he chose the term “Fens,” the Old English word for drained marshy floodlands and “Fenway” for the encircling parkway. Crucial to the project’s success, Richardson designed the gate house, which literally housed the gate that controlled water levels, as well as the bridge for the key crossing at Boylston Street. Richardson’s aesthetic, with variegated raw stone surfaces announcing their innate form and strength, affirmed Olmsted’s larger design goal for the Fens—not to fight but to work with the site’s form and forces: floodlands. Olmsted let the marsh scenery guide his design concept and flow of visitors to circulate along paths and bridges over the deeper (fresher) waters as they met with the Charles River.

Connected via Charlesgate to the city’s older parks, the new Fens were winding and fluid, and quite raw and rustic—a significant shift from the more regimented greenspace Bostonians had come to know on the Commonwealth Avenue Mall, Public Garden, and the nation’s oldest public park, the Boston Common. Rather than straight lines that might pressure speed and efficiency, Olmsted’s curvilinear parks and parkways signalled to slow down, feel the anticipation and discovery of the view around the bend and enjoy “pleasure travel,” whether from the rims of the Fens or more intimate or grander designs to come.

public grounds of distinctive character

Olmsted also made vanguard improvements to the Muddy River, which sprung from Jamaica Pond and trickled toward the Back Bay between two municipalities: Boston and neighboring Brookline. His work, now called the Riverway, not only completely reconstructed a fetid urban waterway as a public greenspace, but involved convincing neighboring leadership to work together on a single landscape, even voting to modify town borders in 1890 to accommodate its winding path. Deeply dredged to improve flow, the shallow ravine allowed for shady walking and bridle paths under crossing bridges, and a narrower parkway above, which ultimately led to the widening Jamaicaway along the Pond, and even wider tree-centered Arborway to the Arboretum and then Franklin Park.

Olmsted’s other waterfront parks not only expanded Bostonians’ access to public health in inventive ways, but were eagerly used. His designs for Pleasure Bay, what became known as Marine Park, introduced an elegant causeway to link South Boston’s City Point to the island on which Fort Independence stood, Castle Island. As the latter was owned by the Federal Government, this required an Act of Congress, but proved worth the effort and expense, as the promenade’s cooling breezes became the most popular part of the park system. And while no longer extant along Boston’s Esplanade, Olmsted’s 1892 Charlesbank design offered a lamp-lit waterfront promenade for relaxation and free public gymnasiums for men, women and children’s outdoor exercise, the first park of its kind in the nation. This access to open space was literally lifesaving for poorer residents in the close quarters of the nearby West End tenements, as Olmsted noted the city’s summer death rates of children with cholera in his park proposal. Likewise, Wood Island Park in East Boston, was also former marshland directly on the water and landfilled by Olmsted’s design into his largest neighborhood park with similar combinations of gymnasisia, playgrounds and walks for immigrant families, initially Irish and then Italian, who called the beloved site “La Montagnella.” The Wood Island land was abruptly taken in the 1960s for the expansion of Logan Airport, which sparked an ongoing park movement in the community.