On September 18 from 12-6pm, Kera Washington and her band, Zili Misik, will put on a celebration to highlight Afro-diasporic arts with interactive dance workshops, performances by three music troupes and the temporary installation of sculptures by Walter Clark. The festival will be held at Pope John Paul II Park on the Neponset River. Olmsted Now talked more with Kera Washington about her project. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Could you introduce yourself and describe your program?

Kera Washington: My name is Kera Washington, and I’m a musician and an educator and an applied ethnomusicologist. I founded a band called Zili Misik in the year 2000, so that’s 22 years ago now. The project that I proposed for Olmsted Now is called “Project Misik: A Neponset River Yard,” and it builds off this idea of bringing people together in interactive, collective music-making experiences—music-making and movement-making experiences—to try to break down people’s dividing lines, all kinds of identities that we carry with us, and to feature folks of African descent and our music-making in the center of activity.

What the day looks like is a day where we have free workshops in movement and music: Afro Brazilian and Afro Haitian dance, and three bands—my band, which is Zili Misik, the Cape Verdean vocalist Lutchinha, and the Haitian roots music band Tjovi Ginen. Of course we have to come together to enjoy food as well, so Gourmet Kreyòl is one of the food trucks that I thought about in Boston, and they will join us as well. We will also have a mobile vaccination clinic. I have a two-year-old—I’m so excited that she can now get vaccinated, and I’m thinking about bringing people together in terms of that healing as well. In this project it has been in the front of my mind that we have to think about each other’s well-being, each other’s health. My spouse got COVID, and I know that because she’s a scientist, she thinks very carefully about all the data that’s coming out about this virus, and I know that she experienced it in a much milder way than had we not had the vaccine. So, that’s important to me. And so is having an art installation be a part of that day. I recently learned about Pneuhaus, which is an inflatable art studio. They create all kinds of shapes of inflatable art and furniture and they have one called street seats, which we will sit on. We will use it for our workshops, and it’s also incredibly beautiful. Walter Clark is a visual artist that I’ve been working with in Project Misik to create hands that represent people playing instruments, especially those that we feature in our workshops. His art will be in the park, leading to our space, to our collective space on the hill in Pope John Paul II Park. So that’s a general idea of what the day will look like. The idea is to bring people together.

Could you talk some more about Project Misik?

I started Project Misik in 2010, after the earthquake happened in Haiti. I reached out to my mentor, Wellesley College Professor Emeritus Gerdès Fleurant, who was my first drum teacher and who had moved back to Mirebalais, Haiti, to found Gawou Ginou King Foundation school and cultural center. He was the person who introduced me to ethnomusicology, to applied ethnomusicology, and he’s the first person who took me to Haiti. Understanding the importance of Haiti, to not just the Black world, but to this whole region of the world, and particularly, the Haitian Revolution to this country and our own Civil War—all of that came from my first interactions with him, and we are still connected today, 30 years later. In 2010, after the earthquake happened, I wanted to go to his cultural center, and I asked him what would be useful. His school and cultural center focuses on music, on folkloric music, and on the healing properties of music. He’s now building a holistic center there as well, which focuses on all types of healing, and it’s right next to the Partners in Health solar-powered hospital that’s there. But in any case, [after the earthquake in 2010,] he said, “Musicians are without their musical instruments. People need music, people need to gather, people need collective healing.” So, we started Project Misik with that in mind, collecting as many instruments as possible, getting donations, going on Craigslist, buying as many as we could afford. And then as a band, as many of us who could go—I think four of the seven of us—went to Mirebalais and to Pétion-Ville, where we had another friend, Madame Emerante des Pradines Morse, who had a school, and we brought some instruments there. We played with people there and left the instruments with the school and with people in the community. And that led to a continuing relationship.

I’m also a Boston Public School teacher. I teach all the kids in the school—the music teacher sees everybody—and I see so many kids carrying so much on their shoulders, so much in their hearts. When they come in my room, a lot of it comes out, because, you know, you’re made vulnerable when you’re making music together. I thought about that idea of collective group lessons, or group music-making, which is the only thing you really can do in a classroom anyway—but I thought about really focusing on that and on particular instruments. So, Project Misik became that—before school, after school, whether it was horns, or whether it was drums, or whether it was guitars, we would focus on a particular instrument, and a particular group of kids.

How did you choose the location for “Project Misik: A Neponset River Yard”?

The way for Zili Misik to make music as a band [at the start of the pandemic] was to gather outside in the neighborhood, in my backyard, and I was really nervous about it. “Are my neighbors gonna be OK with this?” They actually wanted to be a part of it. So, I would invite them over. I had moved into a new neighborhood in 2018, and that’s why this became even more important to me—because I didn’t know my neighbors. I had lived in JP for 20 years. And here I was in Ashmont Adams in a totally new neighborhood that I didn’t know existed the 20 years I was living in JP, and it was still, to me, visibly white. Now that I’ve lived here for a few years, I understand that it’s not, actually it’s a pretty diverse neighborhood, but you don’t see the diversity, what you see is white. And you see great affluence, and then you say, “Hm, well, I know what’s going on here.” There’s great extremes in this neighborhood—as in most of Boston, but it’s really on display in this neighborhood. I wanted to find ways of bringing people together.

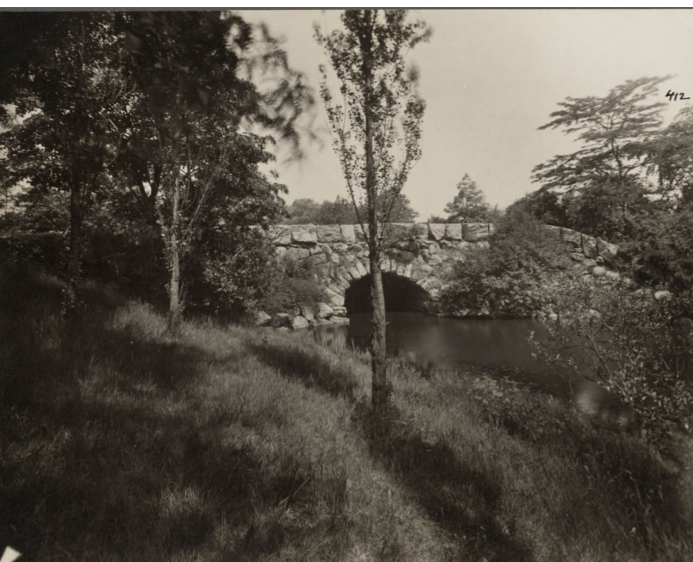

When I moved there in 2018 was also the time when this person decided that he would go on a rant about the “n” word-s and all the people in this neighborhood that he didn’t want to belong here. That was in my mind, also, as the pandemic happened. He is here, and he must have felt comfortable enough to scream it out—so he’s in a neighborhood where he feels like he’s not going to get in “trouble” for doing this. “Trouble”—he’s not going to face any backlash for expressing these views. I see lots of Trump stickers around, but I also see lots of “everybody belongs here” stickers. So, I thought about, “OK, how do we bring people together and get more people to think about how we gather and focus on why Black lives matter”—that’s what was happening at the time, particularly in this neighborhood. When I wrote this grant proposal to Olmsted Now, I already had a little bit of experience doing Project Misik as a community-based, interactive, music-making, free workshops kind of thing with Zimbabwean music, Ghanaian music, Afro Haitian music, and I wanted to expand it and make it bigger. I thought the most beautiful park in my neighborhood is Pope John Paul II Park. Every time I walk in this park, I think about making music with a group of people on the hill there. Not where the playground is, but in the middle of this beautiful—it feels like—wilderness, overlooking the river and thinking about the people who first stewarded this land, including the Neponset of the Massachusett folk. The people who were here before all of us, whose ancestors still continue to shine through the experiences that we have today in this land.

The other reason it’s important for me to talk about the buildup to this is because those concerts that were in my backyard led me to the neighborhood association to talk to people about, “Hey, is this alright with everybody, and can you publicize it?” And then I learned that someone, Erin Caldwell, was interested in doing Dorchfest here—Dorchester Porchfest—as was I, having lived in JP for so long [where JP Porchfest has been held since 2014]. I loved the idea of doing a porchfest. So, we gathered and began to plan for that. And as we were planning Dorchfest, I learned a lot about a lot of musicians in the neighborhood, and I was able to reach out to a lot of people I knew throughout the years to help make this porchfest more diverse. I wanted to continue that relationship with them and bring them to Pope John Paul II Park. I want more brown and Black people that live in Dorchester that don’t know about this park to know this park. I want us to experience the healing that happens in collective music-making—for people of all colors, of course, but I want to introduce more of us Black and brown folk who may not know about this park to experience the beauty of this park.

Why do parks need more equity and spatial justice programming? How does your program speak to that need in Boston parks?

Boston is still a very segregated place. I drive, so I drive through many neighborhoods of Boston, in the Boston area. And yet I still didn’t know about this particular neighborhood [before moving here]. Boston being still a very segregated place, watching people enter my neighborhood who’ve never entered it before makes me happy because I don’t want it to feel like there’s any part of Boston that doesn’t belong to everybody. When I first moved to Boston, I was told not to go to certain areas of Boston because they wouldn’t be safe for me. It’s been 20 years, 30 years, and I know that some people still feel that way. I would like to be a part of changing that. When I think about having this project in Pope John Paul II Park, I think about how I’m a new resident in this neighborhood, and it’s an incredibly beautiful park—one that I didn’t know about before, and I know lots of people don’t know about it.

When I started the permitting process to try to activate this park, I was told it’s not for this type of activity, and that’s what I’m struggling with right now. Because “to keep the status quo” might not be the purpose of deciding only certain types of activities are allowed over here and other activities are allowed in this other park, but that’s the outcome. Because if you’re saying [to me], “No, you have to go over to Hyde Park to have musical performances,” then there’s only music that happens over in Hyde Park, and there’s only soccer that happens over here—and often the arts/activities support each other and can’t/shouldn’t be separated. We should routinely go to Hyde Park and then go to Pope John Paul II and then go to Franklin Park and then go to the Boston Harbor. We should, but we don’t. As a teacher, I recognize so many of my kids have not been out of their five-block radius unless they get on the school bus to go to school—and then they go back home. People proceed with their daily lives and don’t explore. I think it’s so important that we think about how to move people into different neighborhoods, so that we enjoy all of our city.

What about parks and public spaces makes you most grateful?

Public space means anybody can go there. “This land is your land.” However, I understand that, if we are honest, just anybody can’t. I understand that there are still rules about how people are allowed to use public space, and I think those rules should be challenged. I love going to the parks because I feel like I can breathe. I grew up partially in the city, partially in the countryside. Especially going to Pope John Paul II Park, it feels like such an oasis. It’s right there! It’s all this open land, open space on the river. So, that’s what I appreciate, and being able to just see people. When I was there making a video for this grant [application], it was raining a little bit and there was a deer that was sort of hopping off in the distance in the park, and I thought, “Wow.” The reminder that we coexist with other animals, with other beings—it’s important that we have parks and that we go to the parks to allow us to really remember.

What 3-5 words capture the essence of your program?

Collective art celebrating African-diasporic peoples.